I can die happy now.

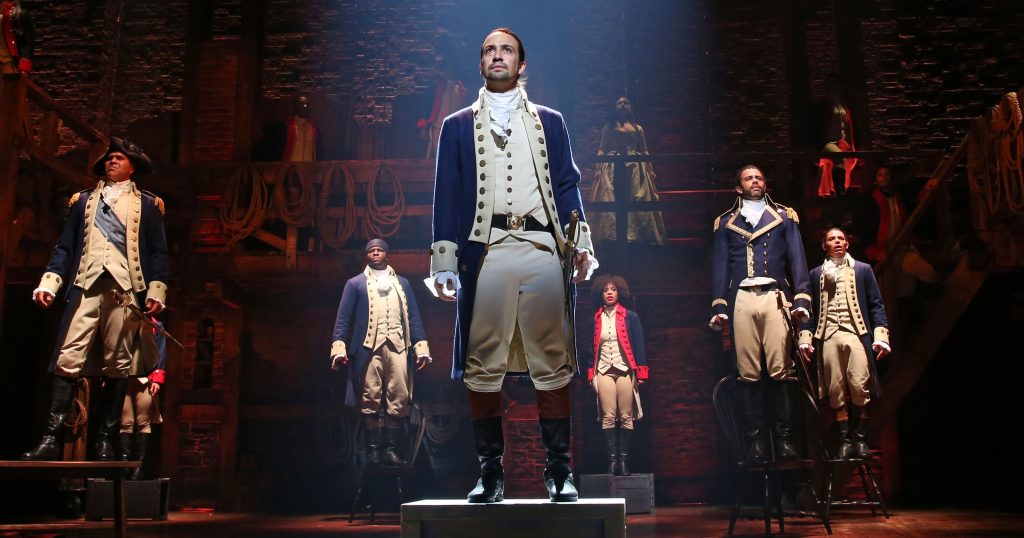

I finally saw the musical Hamilton – a hip-hop rap history lesson on the life of Alexander Hamilton, one the Founding Fathers of the United States of America.

It’s intriguing how by telling the story of any historical figure, we as the audience already know the ending of the story. (Spoiler alert!) He/she eventually dies! Alexander’s rival, Aaron Burr, puts it best when he sings, “Death doesn’t discriminate / Between the sinners and the saints / It takes and it takes and it takes…” Death, indeed, is the one experience common to every human being.

From the opening lines of the show, we learn that all of the odds are stacked against our main protagonist. His father left. His mother passed away. His new guardian died by suicide. With nothing to his name but poverty, death looms quite large.

To Alexander, life seems capped with a strict limit. Facing the uncertain mystery of certain death, he’s not willing to “wait for it.” There are a million things he hasn’t done, so he works “non-stop,” fighting and writing like he’s “running out of time.”

After all is said and won, Alexander hopes that his children will, one day, tell his story. So, with a chance to leave behind a legacy and live on after death in the words of his descendants, he’s “not throwing away his shot.”

Grasping for immortality out of fear of death has been a perennial tendency for man since the very beginning. In the first chapters of the Book of Genesis, immediately after Adam dies the first natural death, his offspring start taking whatever they can from life. They seize power and fame, security and pleasure, and eventually make themselves into “heroes of old,” “men of great renown” (Gen. 6:4).

In response, God floods the entire earth because He knows humanity’s self-led pursuits will not lead to authentic happiness. Rather, only through acceptance of their ‘creatureliness’ – with postures of humility and receptivity to God – will they know true happiness.

To preserve this happiness for us forever, Jesus destroyed death with his own and rose from the dead. No longer was death a reason to fear. No longer was death a limit on life. Death instead became a portal, a passage into eternal life.

When God’s people were suffering in Egypt, enslaved to their work and burdened by death, He rewrote their story. He them free from captivity and led them out where they could rest from work in order to worship, especially on a specific day that He hallowed and set apart.

God intended for Sabbath rest to be a consistent foretaste of our ultimate goal: Heaven, or “eternal rest.”

The Israelites were allowed to work for six days but not on the seventh, or else they would die (cf. Ex. 31:13-16). If any man were to neglect this sacred day of rest, he would lose sight of what truly mattered and then seek after lifeless things, things of lesser or no value.

Returning to our musical, we see how amidst politics, battles, and noise, Alexander Hamilton finally “takes a break” to rest when his wife Eliza announces the good news – the coming of their son. She reminds him, “The fact that you’re alive is a miracle,” and she provides him consolation, saying, “We don’t need a legacy / We don’t need money.” Simply being together “would be enough.”

Nonetheless, Alexander blinds himself with busyness. He excuses himself from family time and chooses to work instead. Overstressed and isolated from his community, he looks to “be satisfied” elsewhere. He engages in a prolonged affair, and it brings death to both his reputation and his marriage.

Alexander confronts his mortality yet again when he watches his son suffer and then breathe his last. Here, death leads Alexander properly, into a posture of stillness and silence.

Now, Alexander “takes the children to church on Sunday,” and he prays; he admits, “that never used to happen before.” He also returns to his wife and stands “by Eliza’s side.” Alexander enters into these Sabbath moments to examine himself and own up to his failings. He takes a “look around,” and remembers the miracle that he exists. All of this strengthens him to seek forgiveness.

Eliza, a character who has been faithful to rest and to her husband, “takes his hand” and restores their brokenness into a new communion. For Alexander, this reconciliation with Eliza is his equivalent of the Flood of Noah’s Ark – a clean slate, a new beginning.

Two scenes later, Eliza calls Alexander “back to sleep;” she calls him away from work to rest. He tragically distances himself again and goes off to work instead. He slips away to duel with his rival, Aaron Burr, and what is the result?

Alexander’s ambition and pursuits lead to his untimely death.

In contrast, Eliza continues on quietly, receptive and humble. She still does not grasp for more than her portion in life. In the final song, Eliza says, “The Lord, in his kindness / … He gives me more time.” She uses this time to care for orphaned children and to promote not her own story but her beloved’s.

From each Sunday lived well, peace and joy overflow into the rest of her week, and these days and weeks constitute a beautifully wholesome life. When the play ends and the curtain closes, Eliza, the only remaining Hamilton, is still alive on stage. As far as the world of theatre is concerned, she is the one who receives eternal life.

How can we hallow our Sundays and take time to consider “who lives, who dies, [W]ho tells our story”?